Interview with Ted Kooser

美国桂冠诗人泰德-库舍访谈录

By Jared Smith, translated by William Marr

作者: 杰雷-史密斯 译者: 非马

NYQ: You discuss many stylistic schools of poetry in The Poetry Home Repair Manual. If you were to describe what it is that defines poetry as such, no matter what its form, how would you do so?

你在《诗室修理手册》中谈到许多诗形式的派别。如果要你描述诗的定义,不管它是什么形式,你会怎么说?

TK: A poem is the record of a discovery, either the discovery or something in the world or within one’s self, or perhaps the discovery of something through the justaposition of sounds and sense within the language. I’ve had that sentence written on a slip of paper and taped above my desk for several years, and I think I wrote it myself, but perhaps I found it somewhere.

一首诗是对一个发现的记录,无论这发现是这世上或你自己心中的某种东西,或经由语言中并列的声音与意义所发现的东西。我把这句子写在一张纸条上贴在我的桌上好几年了,我想是我自己写的,但也可能是我在什么地方找到的。

NYQ: Is that definition in evidence as much as you would like in today’s poetry journals?

你这定义是否能在当今的诗刊上找到充分的证据?

TK: Yes, I think that nearly all of the poems we might consider could be fit into it.

是的,我想几乎所有我们能考虑到的诗都与它相符。

NYQ: Your own poetry frequently moves from the smallest details out into a bigger and more generalized feeling about things. How do you select the details you’re going to keep in a poem?

你自己的诗常从最微小的细节移入一个对事物有较大及较广泛的意义。你如何 选择你要保存在一首诗中的细节?

TK: All of the details should in some way contribute to the overall effect of the poem. I don’t like to keep any details that aren’t essential parts of the poem’s clockworks. Part of my process of revision is to eliminate the extra parts.

所有细节都必须多多少少对诗的整体效果做出贡献。我不喜欢留下任何对诗的组成无关紧要的部分。我的修改过程中有一部分便是删除多余的部分。

NYQ: How do you know when you’ve finished revising a poem?

你怎么知道你完成了修改一首诗?

TK: I think it was Auden who said we never finish a poem, we just abandon it, and that’s a wise observation. I usually work on a poem until I can’t see anything else to do that might improve it. Then I let it sit for as long as I can stand to and look at it again.

我想是奥登说的,我们从未完成一首诗,我们只是把它放弃,那是明智的观察。我通常对一首诗下功夫一直到我看不出还能改进什么为止。然后我让它留在那里直到我无法忍受了再把它从头看一遍。

NYQ: Do you have poems that get lost during the revision process?

在修改过程中你有无遗落过一些诗?

TK: I’ve revised a lot of poems into a comatose state. Some of them I can revive by going back to early drafts and starting from there. Some die on the table. The danger of too much revision is that the resulting work can be perfectly written but altogether bloodless.

我曾把许多诗修改成昏死状态。有些我可以回到它们的初稿去重新救活。有些则死在手术台上。过分修改的危险是成品可能完好,却毫无血气。

NYQ: Often your poems move across time, carrying the reader with them so that the detailed object of one time or space reverberates in another time with tangible consequences. For example, in your poem “The Ice Cave,” a chip of ice that was meant to be used for keeping food fresh becomes a cool evening wind which blows shadows from the past through a family going about its daily rituals. Or in “Pearl,” where the drawn blinds within a house allow just enough light and shadow to create ghosts that count the tea cups and the silverware. We’ve all had that sort of feeling or awareness. We’ve all felt detailed objects from one time reverberate into another, but it takes a very accomplished poet to remind us of its legitimacy. How do you transport an image from one time or place into another?

你的诗经常越过时间的界线,把读者从一个时间或空间带进另一个时间,让一些细节在那里震荡出可触可摸的结果来。譬如在你那首<冰窟>的诗里,一块用来为食物保鲜的冰块却变成了一阵冷冽的晚风,把过去的阴影吹掠过一个日常的家庭。或在<珍珠>里,拉起的窗帘把恰好的光与影透进来创造出一些幽魂,在屋子里点数茶杯与银器。我们都有过同样的感觉与认知。我们都感到过来自一个时间的细节在另一个时间里震荡,但我们需要一个深有成就的诗人来提醒我们它的合理性。你如何把一个意象从一个时间或地点传送到另一个?

TK: You know, I really don’t know how all that happens. Once I’m writing, those associations and effects just come to me. I’d guess this is the result of having had 45 years of experience making decisions about poems and, now, all those decisions are a part of my experience that is brought into play.

你知道,我实在不知道它们怎么发生的。一旦我开始写,那些联想与效果便自动来到。我猜这是45年对诗的决策所产生的经验,所有那些决策现在都成为我经验的一部分,并发生作用。

NYQ: Why are these objects so important to us?

为什么这些东西对我们那么重要?

TK: Lots of more articulate poets than I have talked about the inherent qualities of things, Neruda, for example. I can’t just now put my hands on any of those quotes. But don’t we all attach feelings to inanimate objects? All across the arid Great Plains there are farmhouses in which there are sea shells sitting on end tables or in china cabinets. Each of those has, or had, a significant meaning to the person who brought it all the way home from a seaside vacation. They are imbued with life because of the associations.

许多比我更能言善道的诗人曾谈过事物的本质,例如聂鲁达。我此刻手边没有这些引言。可是我们不都把感情附丽在没有生命的东西上面?在干旱的大草原上,常可看到一些农舍,里面的茶几上或碗柜内摆着贝壳。它们每一只都有,或曾有过对那些老远从度假的海边把它带回家的特殊意义。因为这些关系,它们都充满了生命。

NYQ: What marks a poet as a “beginning poet” rather than an accomplished one? Is it a sense of balance as well as word choice?

什么东西把一个诗人区分为“起步”诗人而非熟练诗人?是平衡的感觉以及语言的选择吗?

TK: Of course, we poets are never done with our learning. I don’t know Stanley Kunitz but I’d guess even at his grand old age he is still making important discoveries while writing. Beginning and accomplished are generalizations. Perhaps the beginning poets are the ones making the most discoveries, are having the biggest number of revelations coming at them as they read and write, and the accomplished poets are making fewer discoveries, having so many discoveries already behind them.

当然咯,我们诗人永远学不完。我不知道斯丹利?康尼兹 Stanley Kunitz 但我猜想即使在他那样的大年纪他依然在写作时会有重要的发现。起步及熟练是概括的词语。也许那些刚起步的诗人在他们写与读时有最多最大的发现,而那些熟练的诗人在他们已经有许多发现之后,则越来越少有新的发现。

NYQ: Your poems are frequently conversational in tone as if you were talking with someone who is close to you, and yet there is a sense of your being isolated. Is it important to your creative process to spend time outside, walking the fields by yourself?

你的诗通常带有对话的口气有如你在同你身边的人讲话,但却予人以孤独的感觉。你是不是觉得很重要,在你的创作过程中你需要花时间在外头,独自一个人在田野里走动?

TK: I have always enjoyed being alone, amusing myself, completely in control of my time. My poems are not spoken to a reader walking beside me, but one at some distance, as if he or she were being approached by a letter I’d written.

我通常喜欢孤单,独乐,完全控制自己的时间。我的诗不对走在我身边的读者说话,而是保持一点距离,有如接近他或她的是我写的一封信。

NYQ: Do you carry a pen and notebook with you to jot down stray thoughts and observations, or do you work from what you bring back in your memory at the end of the day?

你随身带着笔同记事本把你流动的思绪与观察写下来呢,或在每天终了时凭你的回忆写作?

TK: I always have a scrap of paper in a pocket, and from time to time write down a reminder, but I can usually remember my observations long enough to put them to use.

我通常口袋里总带着一叠纸,不时写下提要,但我一般都能把记忆中的观察派上用场。

NYQ: You were successful in business for many years even while you wrote. One might think that the kind of keen observation a poet needs to write as you do would be valuable to business, yet I don’t know of many businesses that place much value in poets in general. Why do you think that is?

你在企业界成功多年,即使在你一边写作的时候。人们也许会以为像你这样的诗人所具有的敏锐观察能力对企业会有好处,但一般说起来,我不知道有多少企业界对诗人的价值有所认知。这是什么原因?

TK: Companies hire people who can help them succeed, and most companies wouldn’t see how poets could do that. Industry looks for personnel trained to advance industry, and poets aren’t trained for that. It was in many ways a fluke that I was ever hired into business. I’d never had a business course or been interested in business. I just needed an income so I could write poems before and after work. The man who first hired me took a big risk. I succeeded, though, because I was good at writing, could write articulate memoranda, letters, manuals, ad copy, and so on. Business schools are good at teaching management techniques, but they aren’t very good at preparing potential employees to be skilled communicators.

一般公司雇人来帮助他们成功,大部分的公司看不出诗人如何能做到这一点。工业界找那些受过促进工业训练的人,而诗人并没受过那种训练。从许多方面来说,我受雇进入企业界是一种侥幸。我从未学过一门商业课程,对商业也没兴趣。我只是需要一份薪水让我能在上班的时间之外写诗。但我成功了,因为我会写,能写通顺的备忘录,信件,手册,广告等等。商业学校善于教管理技术,但他们并不善于训练未来员工的沟通技艺。

NYQ: What about the creative process itself? Some years back, Arthur Koestler suggested in The Act of Creation that acts of artistic creation come from the same kind of thought processes that scientists use in theoretical work. Do you find yourself using the same kinds of thought process in creating a poem as you used in approaching a business opportunity?

关于创造性过程本身呢?几年前,阿舍?寇斯特乐 Arthur Koestler在他的《创 造的行为》里提议说艺术的创作同科学家在理论工作上所使用的是同样的思考过程。你是否发现你在创作一首诗时同你在处理一个商业机会时使用相同的思考过程?

TK: I don’t really understand the scientific mind, but I have a new friend who is a noted scientist and I hope to learn some things about how they think. Somehow, though, it seems that creative people in all fields have earned the license to be dreamers. Einstein is a good example of somebody who was often lost in dreams, as I recall. When I worked in business, I came up with some pretty creative ideas, or so they seemed to me, and they arose out of the same dreaminess that I indulge in as a poet.

我真的不了解科学的心灵,但我有一位新朋友是著名的科学家,我希望从他那里听到一些他们的想法。可是不知何故,在每个领域里有创造能力的人似乎都拥有梦想者的执照。据我所知,爱恩思坦是个经常在梦想中迷失的好例子。当我在商业界工作的时候,我想到了一些相当有创造性的念头,至少我认为它们是如此,它们就来自我作为诗人所沉湎的相同的梦想。

NYQ: You quote William Butler Yeats as saying “The aim of the poet and the poetry is finally to be of service, to ply the effort of the individual work into the larger work of the community as a whole.” “That’s good enough to cut out and pin up over your typewriter,” you say. I heartily agree. Why do poets have so much trouble doing that in today’s society?

你曾引用过叶芝所说的:“诗人与诗歌的终极目的是服务,努力把个人的工作提供给更大的群体的工作。”“善哉斯言!你该把它剪下来贴在你的打字机上,”你说。我全心同意。为什么诗人在今天的社会上很难做到这一点?

TK: A number of our poets aren’t interested in giving something to “the community as a whole.” They are mainly interested in creating works for their own smaller communities, audiences of sophisticated literary readers. That’s their choice.

我们有些诗人对提供东西给“社会群体”不感兴趣。他们主要只对为他们的小圈子,精致文学读者听众而创作感兴趣。那是他们的选择。

NYQ: What about the gathering of material for poetry? That goes on best outside the classroom, doesn’t it, without any preconception of where you will find it?

你对为诗搜集材料有何想法?那最好是在课堂外进行,不是吗?不存有在什么地方才能找到的偏见。

TK: Paying attention to what’s under your nose is essential, isn’t it? Wherever you are, whatever you’re doing. I spoke a minute ago about creative people being dreamers, but between sessions of dream they need to pay attention to what’s under their noses. We spend too much of our time preoccupied with what has happened, or what might happen next.

注意当前的事物是绝对必要的,不是吗?不管你身在何处,不管你在干什么。我不久以前才说过有创造能力的人都是些梦想者。但在梦与梦之间,他们必须注意到他们眼前的东西。我们对过去及未来的事物花费了太多的时间。

NYQ: One of my favorite poems of yours finds very telling material in the office place. It’s a poem about secretaries singing to each other all day through the use of the office equipment as well as through their calls to each other on behalf of the business at hand…but also in support of each other whenever one is hurt or in pain. It is poetry from a day-to-day world of hard-fought survival that a majority of Americans face but that hasn’t been addressed to a great extent in past poetry. It seems to address a haunting balance of sacrifice and support that permeates relationships where people give of themselves for a corporation. Can you comment on that?

在我喜爱的你的诗当中有一首很生动地描写了办公厅里的事。那是一首关于秘书们通过办公室的器具以及手边的公事整天互相酬唱…但每当有人受伤或受苦时也彼此扶持。它是大多数美国人每天面对的挣扎求生的世界,但在过去的诗里很少被提及。它似乎触及了一个在牺牲与支持之间的令人困扰的平衡,渗透到人们把他们自己献给公司的那种关系。你能否谈谈这个?

TK: Most people are trying to do as best they can, to do the right thing, sometimes against great odds, including their own limitations. That goes for workers at all levels in businesses, for faculty and staff of universities, for government workers, for military people. There are few of us who are truly evil, who mean to do harm. I once asked a jailer who worked at the county facility that processes killers for death row at Huntsville, Texas, how many of the murderers he’d met—and he’d met hundreds— were genuinely evil and he said, maybe five percent. The rest, he said, had just made stupid choices.

大多数的人都试着想把事情做好,做对,有时候冒着不利的条件,包括他们本身的限制。这适用于商业界各个阶层,大学的教职员,政府机构的员工,以及军人。我们之中很少人是真的邪恶,想伤害别人。我有一次问在德克萨斯州的罕斯维尔关杀人犯的死牢里工作的一个狱卒,他所见到的成百的杀人犯当中有多少是真邪恶的,他说,也许有百分之五。其余的,他说,只是作了愚蠢的选择。

NYQ: I suppose the same kind of question should be asked about other ways of earning a living, whether farming or washing windows or being a housewife. The editor of Vagabond magazine, a good literary mag. from some years back, earns his living as a window washer on the west coast. These voices are important to the American voice, aren’t they?

对于那些用其它的方式谋生,不管是种田或洗窗子或当家庭主妇,我想也该问问同样的问题。《流浪者》,一本好的文学杂志的编辑几年前在西岸靠洗窗子过活。这些声音对美国的声音来说是重要的,不是吗?

TK: An articulate voice from any quarter should be welcomed.

来自任何角落的铿锵声音都该受欢迎。

NYQ: This expanded inclusiveness seems to be something you are quite committed to building during your tenure as Poet Laureate, and it is a very worthy one. Do you have other key objectives as well that you hope the position can help you achieve?

这种扩大的包容似乎是你在桂冠诗人任内想要营造的,这是很有价值的事。还有其它的目标你希望你的位置能帮你完成的吗?

TK: I’d like to show people that they needn’t be afraid that when they enjoy reading a poem some teacher is going to pop up and ask them why they enjoy it, and give them a bad grade because they can’t quite say. If we taught poems as experience, rather than as puzzles that must be solved by one right answer, I think a lot more people would be reading poetry.

我要让人们明白,在他们津津有味地读一首诗的时候,他们不用担心会有老师突然出现并问他们为什么喜欢它,给他们一个坏分数要是他们答不出来。如果我们用经验来教诗,而不是当成只有一个正确答案的谜来解,我想会有更多的人来读诗。

NYQ: Do you feel under any increased pressure to guide your work even more closely now that you have been designated Poet Laureate? Are there hidden responsibilities most poets might not be aware of?

现在你是桂冠诗人,你会感到对你的工作有更多的压力吗?有没有一般诗人所不知道的隐藏的责任?

TK: I’m not going to submit any poems to magazines for a good long while because right now it’s likely that somebody is going to publish them just because I’m Poet Laureate and not because they’re good poems. I suppose I’ll be facing this the rest of my life, and I’ve played with the idea of taking on a pseudonym. In a few years, maybe I can cautiously submit some things again, with my name on them. I also have sworn off writing blurbs and letters of recommendation and so on because I don’t want to be throwing the title around.

我会有一段长时间不给杂志投稿,现在有人会因为我是桂冠诗人而不是因为它们是好诗而刊登它们。我猜在我有生之年会一直碰到这个问题,我曾考虑使用笔名。也许再过几年,我能慎重地再度投稿,在它们上面使用我自己的名字。我同时也放弃写推荐信及介绍函这类东西,因为我不想把衔头到处去招摇。

NYQ: There are some positive things our government has done to encourage poetic development in recent years. Yet many have said that government support is inimical to artistic development. What do you think of government support for the arts generally?

我们的政府近年来在鼓励诗的发展方面做了一些积极的工作。但许多人说政府的支助对艺术发展有一种负面的作用。你对政府支助艺术一般来说有什么想法?

TK: I believe in government support for the arts, and hope it will continue. I think it may be more helpful in the long run to have support for programs than grants to individual writers, but I could be wrong about that. It takes but a tiny part of tax revenue to do a lot of good for the arts. But private support is also very important. The Poet Laureateship and the Poetry and Literature Program at the Library of Congress, for example, are funded wholly by private endowments, and to support its other programs the Library works hard to secure private support.

我对政府支助艺术有信心,希望它会继续下去。我想长期来说,支助各种计划比支助个别的作家会更有助益,但我的想法可能不对。只需用纳税人很小一部分的钱便能对艺术做出许多好事来。但私人支助也很重要。例如,国会图书馆里桂冠诗人这个职位以及诗与文学的计划,都是靠私人捐助的钱来维持,而为了支持其它计划,图书馆也努力争取私人的捐助。

NYQ: You say in The Poetry Home Repair Manual that poetry is always about communication, and that it is important to keep in mind a particular person or audience you are speaking to while writing. Do you think that the audience most of us write to today is a smaller and more elite group than it might be?

你在《诗室修理手册》里说诗永远是为了沟通,在你写作的时候你在心中必须有个特定的对象。你认为今天我们大多数人的写作对象是一个较小也较精英的集团吗?

TK: Most of the poems we see in the noted quarterlies is directed to a sophisticated literary audience, and most of those journals have small circulations, 500-1000 subscribers, perhaps. A miniscule proportion of the population knows about the existence of literary magazines, but those magazines and those writers are a vital part of our social order. That small literary community, of course, is just one of the several communities of poetry. The others are cowboy poetry, slam poetry, rap poetry, and so on. Rap poetry may have the biggest community because we all hear it being played on car radios everywhere we go. None of these communities has much interest in or tolerance for the others, but writers make choices as to which community they want to write for, and their choices should be respected.

我们看到的许多在有名的季刊上发表的诗都是针对一些有文学品味的听众,而这些刊物的发行量一般都很小,从500到1000个订户,也许。只有一小部分的人口知道这些文学杂志的存在,但那些杂志同那些作家是我们的社会秩序中至关重要的成分。那个小的文学圈子,当然咯,只是众多诗圈子中的一个。其它的是牛仔诗,撞击诗,吟唱诗,等等。吟唱诗可能是圈子最大的一个因为任何地方我们都在汽车收音机里听到。这些圈子对别的圈子都没什么兴趣或耐心,不过作者们选择他们各自的写作圈子,他们的选择该受到尊重。

NYQ: When you talk about craft in writing, and when you talk about home repair of poetry, you seem to be stressing much more than poetic forms—such as pantoums or sestinas. At one point you call such forms merely exercises, and at another you stress that a poem that is forced into a set form may easily end up looking like chunks of ham thrown into a Styrofoam container. Yet you also stress the importance of forms and prosody in polishing and revising poetry. Would you comment on that?

当你谈到写诗的技巧的时候,还有当你谈到诗的修理的时候,你似乎在强调比诗的形式更多的东西──诸如隔行同韵的四行诗或六节诗。你在某处把这些形式称为仅仅是一种练习,而在别处又强调说一首被硬摆进某种固定形式的诗很容易成为看起来像几块火腿被丢进一个塑料盒子里。可你又强调形式与诗体论对润饰修改诗的重要性。你能否对此发表点意见?

TK: Somewhere in that book, perhaps in the section to which you’re referring, I quote John Berger as saying that form ought to be inevitable. I might go on to say that form should be so deeply integrated into writing that it can’t be separated from it. Yet lots of less successful formal poems are of two parts, the poetry and the form, clearly evident. One or the other part usually has the upper hand. Form in the most moving poems is neatly integrated, but is there. It’s not the first thing we notice. Frost’s Stopping by Woods… is a good example of a poem written in form that seems perfectly integrated with the poetry. Richard Wilbur is our living model for that kind of a poem. Most readers would not notice the form at all, I suspect. They’re absorbed by the whole experience, by the poetry.

也许就在你提到的那个章节里,我引用了约翰?博格 John Berger 的话,说形 式应该是不可避免的。我可以接着说形式该被深深地融入作品里去而无法分割。但许多不太成功的格律诗都有两部分,诗与形式,泾渭分明。两者之间总有一个占上风。形式在最动人的诗里被很巧妙地融为一体,但它的确在那里。它不是我们一眼便看到的东西。佛洛斯特的<在林边停驻>是个好例子,一首用格律的形式写出,却完美地与诗相结合的作品。理查?威尔伯 Richard Wilbur 是那类诗的活样板。大多数的读者根本不会觉察到形式,我猜。他们全神贯注于整个经验,于诗。

NYQ: In your Poetry Home Repair Manual, you say “We teach ourselves to write the kinds of poems we like to read.” What do we learn from poetry classes?

在你的《诗室修理手册》里,你说“我们教导我们自己写那种我们爱读的诗。”我们从写诗班学到些什么东西?

TK: Good teachers can direct us toward works that we might not otherwise encounter. I can’t emphasize enough how important it is to read.

好的教师能指引我们去接触那些我们可能错过的作品。我极力强调阅读的重要。

NYQ: You also say “We serve each poem we write. We make ourselves subservient to our poetry. Any well-made poem is worth a whole lot more to the world than the person who wrote it.” This might suggest that you don’t think much of the current idea that seems popular in media that poetry is “just entertainment?”

你还说“我们伺候我们写的每一首诗。我们使我们屈从于我们的诗。任何好诗比写它的那个人对世界的价值要大得多多。”这说法是否表示你对在媒体上似乎颇为流行的,把诗当成“仅仅是娱乐”的观念不以为然?

TK: I meant to say that we put too much emphasis on celebrity. Some of the poems we see today, by living American poets, will disappear when the poet dies because the poems are so attached to the poet’s public persona. Some of this is due to the popularity of poetry readings, at which the poets are what is on display, rather than their poems. Readings are useful, of course, in showing an audience how the poet thinks his or her poem should be read.

我想说的是,我们过分强调了名人。我们今天看到的一些活着的美国诗人所写的诗,将在诗人死后消失,因为那些诗是如此地附丽于诗人的社会身份上。有些是因为诗朗诵会的流行,在那里展出的是诗人,而不是他们的诗。朗诵有它的好处,当然,让听众了解诗人觉得他或她的诗该如何被读。

NYQ: And yet, as you point out, poetry does have to be entertaining, or at least polite enough to be invited into peoples’ living rooms?

然而,正如你所指出的,诗必须有趣,或至少优雅得可被邀请到人们的客厅里?

TK: If a poem doesn’t engage a reader’s interest, it’s going nowhere.

如果一首诗引不起读者的兴趣,它便走不到哪里去。

NYQ: What sort of different creative dynamics have you observed between longtime poets who have worked largely outside of academic circles such as yourself, and those who have served mainly as academics?

对那些像你自己一样长期在学院之外工作的诗人,同那些主要在学院里服务的诗人,你看出他们之间有什么不同的创作动力吗?

TK: I wish I were better equipped to answer that. There are very few living poets, that is, poets who are publishing quality work, who have worked outside universities, and I know of only a handful. I’ve never had any sustained, substantive correspondence with another businessman poet, for example. One of my best friends, Jim Harrison, has lived and written outside the universities and has been very successful, but he hasn’t made enough money as a poet to be comfortable. His income has come from his novels, novellas, and Hollywood work.

我希望我能有更多的资格来回答这问题。很少现存的诗人,我是说,出版过高品质作品的诗人,在大学之外工作,我只认识有数的几位。例如,我从未同另一位经商的诗人有过长期的、实质的交往。我最好的朋友之一,吉姆?哈里森 Jim Harrison,在大学外面生活并写作,而且很成功,但他并没以诗人的身份 赚够过舒适生活的钱。他的收入来自他的长篇小说,中短篇小说,以及好莱坞的工作。

NYQ: What role does the study of poetry and literature from past times or other cultures play in writing poetry today?

研究过去或其它文化里的诗与文学,对今天写诗扮演什么样的角色?

TK: I say in my book that poets ought to be reading all kinds of poems, old and new, and that we learn from everything we read. There is value to a creative writer in reading anything and everything.

我在我书里说过,诗人该读各式各样的诗,旧的与新的,我们从我们读到的每样东西里学习。读任何东西读每样东西对一位创作者来说都是有价值的。

NYQ: A lot of poetry being written today seems to deal more with the poet writing it than with what is outside of the poet that might seem likely to have relevance to readers who don’t know the poet. Is that a passing phase we are going through?

当今有许多诗似乎对写它的诗人本身比对在诗人之外的其他不认识这诗人的读者更有关联更有意义。这是不是我们正经历的暂时阶段?

TK: It does seem that a great deal of our poetry is self-referential, and the rule of fashion is that once a few influential people turn in one direction more are likely to follow. But I wouldn’t say that these poems aren’t relevant to their audience, which may be self-referential, too. Time will sort all this out. As to whether the poems you’re asking about will endure, they well may, as mirrors of our self-referential times.

看起来我们的许多诗是自我关照,而风尚的规律是一旦几个有影响力的人转往一个方向,更多的人便会跟随。但我不认为这些诗对它们的读者无关痛痒,即使是自我关照。时间会把这一切过滤拣选。至于你问这些诗是否会持久,它们可能会,作为我们这个自我关照时代的镜子。

NYQ: All poets project a degree of presence in their poetry. As a poet matures, you have suggested, that presence will usually reflect less of the poet and more of the background of his or her material. You compare this changing effect to looking through a window and perceiving different amounts of reflection on the glass depending on the degree of backlighting. Are there any steps you took as a young poet to encourage this ability to decrease your presence in looking out at what was important to you?

所有诗人在他们的诗里都或多或少投射了存在。当一个诗人成熟了,你曾说,这个存在通常会较少反映诗人而更多地反映他或她的材料的背景。你把这种变化同从窗里看出去,因不同程度的逆光而感知在玻璃上不同的反射相比。作为年轻诗人,你采取过什么步骤来鼓励这种能力,在找寻那些对你重要的东西的时候,减少你的存在吗?

TK: If I suggested that the maturation of all poets follows the track you’ve described in your second sentence, I didn’t do a very good job of writing, because each of us grows differently. There are, of course, examples of poets whose work, as they matured, showed more and more of their presence. But others have gone in the other direction. In that section of the book I was trying to develop a metaphor that could describe the degree to which the poet’s presence is evident in single poems.

如果我暗示过所有诗人的成熟都遵循你在第二个句子中所描述的轨道,那便是我没写好,因为我们每个人的成长都不相同。有许多诗人,当然,当他们成熟了,显示了他们越来越多的存在。但别的诗人则走另一个方向。在我的书里,我试图建立一个隐喻来描述诗人显示在诗中的存在程度。

NYQ: It can be hard for younger poets to find markets for their work simply because there aren’t many markets available to them at their local bookstores. While Len Fulton’s Directory of Small Presses covers a huge number of potential markets, it’s hard to know from the listings what the poems in a particular journal are like. In the 50s and 60s, we used to be able to walk into independent bookstores and browse through poetry mags. until we found ones we were comfortable with. What can a young poet do today to help himself or herself along in that regard?

年轻诗人很难为他们的作品找到市场,因为当地的书店没提供什么市场。虽然《小出版商目录》里面有大量可能的市场,但很难从列表里知道某个刊物喜欢什么样的诗。在五十及六十年代,我们可走进独立经营的书店去浏览各种诗刊,直到我们找到一些我们觉得比较合适的。今天的年轻诗人在这方面能怎么办呢?

TK: We ought to be supporting our literary magazines, and one way to do it is to purchase copies. Before a poet submits to a journal he or she is unfamiliar with, I suggest writing to the journal and purchasing a copy.

我们应该支持我们的文学杂志,一个办法是去买它几册。诗人在对一个他或她不熟悉的刊物投稿前,我建议写信给刊物去买一册。

NYQ: Do computers and the Internet aid in communication, or do they hurt it?

电脑及网络有助于沟通呢,或有所伤害?

TK: Most of my writer friends are now using computers for our manuscripts, and e-mail for some of their correspondence. Some of my best friends, like Jim Harrison and Danny Marion and Leonard Nathan still write handwritten letters and it’s an honor to receive them. My iMac has certainly helped me write prose. I might never have finished my book, Local Wonders; Seasons in the Bohemian Alps, if I’d had to do it on a typewriter. I was always so devoted to having perfect manuscripts that when I made an error halfway down a page I’d rip the sheet out of the carriage and start all over. I’d still be doing that if I hadn’t had the computer to make corrections easier.

我大部分的作家朋友现在都用电脑写作,用电邮传递他们的一些信件。我一些最好的朋友,如 Jim Harrison , Danny Marion 以及 Leonard Nathan 还用手写信,收到这些信是一种荣幸。我的 iMac 确实在我写散文时帮了 我不少忙。如果要我用打字机,我也许永远不会完成我的《当地奇观》及《波西米亚阿尔卑斯山的季节》这两本书。我通常对稿件很挑剔,当我在半途中间出了错,我会把整页从打字机托架上扯下,重新来过。要是没有电脑让改错变得那么容易,我大概现在还在写它们。

NYQ: Thank you, Ted. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

谢谢你,泰德。你有没有别的东西要加的?

TK: I hope that nowhere in this interview have I made it sound as if my way of looking at writing is the one right way. Each writer is different, and each beginning writer, one hopes, will in time find his or her own way.

Thank you very much for your close attention to what I’ve said in my published writing and for letting me expand upon that here.

我希望在这访问里我不曾说过什么话听起来像是我对写作的看法是唯一的正途。每个作者都不同,而每一个刚开始写作的人,我们希望,将迟早会找到他或她自己的路子。

非常谢谢你那么留意我在发表的作品里所说的话,并让我在这里作些补充。

Note: Ted Kooser is the 13th Poet Laureate of the United States. English version of this interview was first published in The New York Quarterly, Issue No. 62, Spring, 2006. Reproduced by permission of The New York Quarterly. The Chinese version of this interview is translated by William Marr.

译者注:这篇访问录译自芝加哥诗人杰雷-史密斯(JARED SMITH)于2005年1月28日对美国国会图书馆桂冠诗人泰德-库舍(TED KOOSER)的访问。原文发表于《纽约季刊》第62期,2006年春季。经《纽约季刊》允许转载。

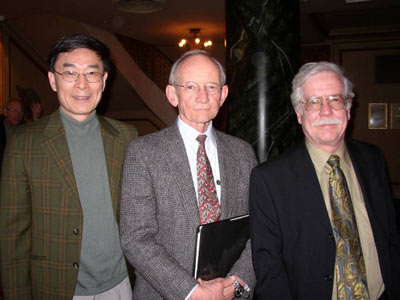

Photo by Glenna Holloway, March 2006.

From left to right: William Marr, Ted Kooser, Jared Smith.

Posted June 22, 2006

|